Author: gorgeousgael

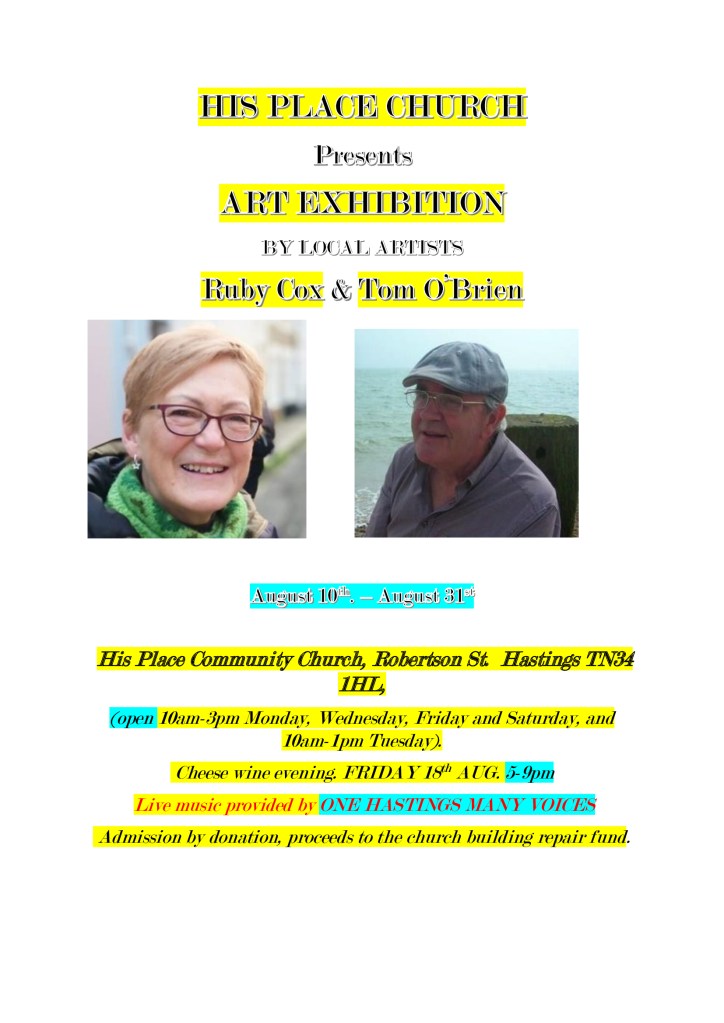

ART EXHIBITION

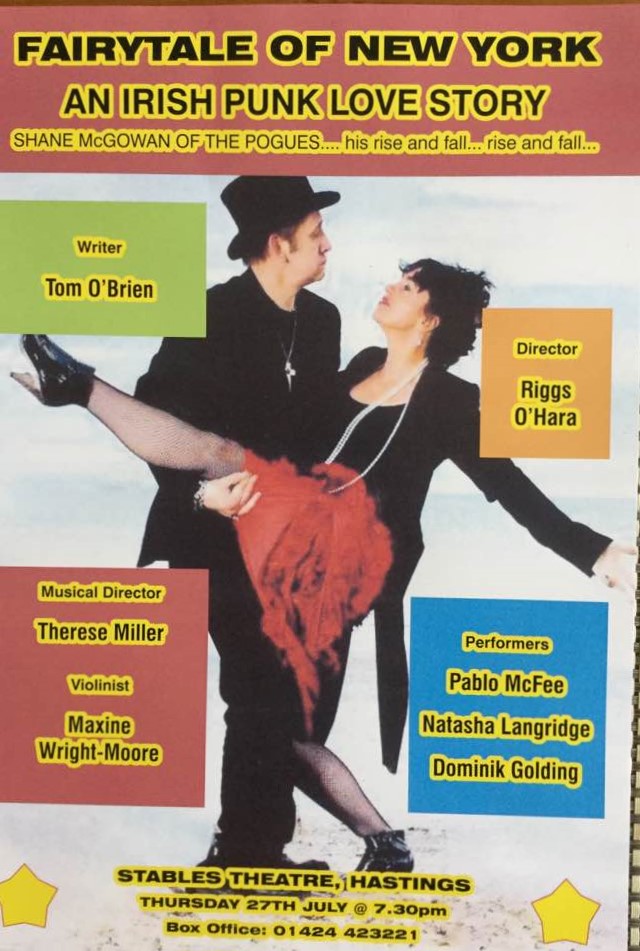

FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK

STABLES THEATRE – THURS 27th JULY

BOOK NOW – TICKETS SELLING FAST!

THE HOMECOMING…a short story

THE HOMECOMING

Did you ever see a hill shrink? I mean get physically smaller bit by bit until there was nothing left. To an occasional observer like myself it was probably more of a culture shock than if I had been present throughout its gradual disintegration. But then, I only saw it every few years or so – when I came home on holidays from New York. And every time there was another big chunk of it gone. Things like that tend to stick in your mind.

It’s hard to describe how I felt about that hill. It was like one of the family. I grew up with it. In the morning when I woke it would be there, looking down into our haggard. A Jekyl and Hyde character; in the winter dark and foreboding, the mists clinging to its girth; in the summer smiling down on us children, beckoning us up into its warm embrace.

It never had a name, just The Hill. Mornings, before we left for school, mother would shout at one of us to run to the Hill and fetch some milk from Nellie. Nellie was our goat, and I think she liked The Hill better than our haggard. The grazing wasn’t any sweeter up there, she just like the view.

She wasn’t the only one. In summer we couldn’t wait to get home from school, divest ourselves of our school clothes, and climb up there. There were five of us; my brother Seamus and myself, Frances and her two brothers, Billy and Josie. We called our gang the Red Devils, which had Fr Dunphy sucking on his teeth when he first heard mention of the name. Frances was always kissing me, which I didn’t care much for at the time.

The Hill was our territory. Nobody could play there unless we invited them. Once, we fought a running battle with some other kids who tried to muscle in. We soon scattered them with a hail of stones. That battle established it as our kingdom. My father said we almost owned it anyway; the big farmer to whom it really belonged letting him have the use of it for ten shillings a year.

Clustered round its bottom were whitewashed cottages, the occasional bungalow, the pub, the creamery, and a galvanised shack occupied by a witch. Behind the hill ran the railway line, and the level crossing, which was manned by Frances’ father. Their house was part of the railway, and their front room was a mass of levers and cables.

We had a secret place on the Hill, a cave beneath an outcrop near its top. You had to crawl on your belly to gain entrance because its mouth was guarded by several scraggy furze bushes. We could have cut them down of course, but then we could have hidden inside and watched the goings-on below us.

The pub was the centre of the social activity. On summers evenings there was open-air dancing on a makeshift stage in the field adjacent to the pub. Old time waltzes and set dances were the favourites. The accordion player sat on a chair playing his tunes, polishing off large bottles of porter as fast as they were put in front of him. If playing was thirsty work then dancing was thirstier, and there was a constant stream of revellers shunting between pub and dance area. From our vantage point we watched the dancers fling back their heads and swing their partners round and round, their shoes pounding on the timber, their shouts of joys ripping through the warm summer’s evening.

In the winter, the travelling shows came and pitched their tents in the same field, and entertained us for a few weeks with a mixture of comedy, drama and music. Badly-acted plays and out-of-key singers warmed us up on many a cold night at the foot of the Hill.

My cousin, Nora, took a fancy to one of the travelling showmen and began taking him up to our hiding place when the show was over. We didn’t think much of that. One summer’s evening we heard her screaming up on the Hill. We found her in the cave, surrounded by a pool of blood. When the doctor came he took away something in a bag, and later on I saw my father heading across the fields with a shovel on his shoulder. The show never came by again.

As we grew older I began returning Francis’s kisses. Now it was our turn to use the cave late at night!

I had just turned seventeen when the bulldozers moved in. Shortly afterwards explosive experts began blowing up bits of the Hill, and the quarrying began in earnest. Soon there was a sprawling complex of dust-shrouded buildings, machines eating away at the Hill, and convoys of trucks bumping across the stony ground. Before long, the trees had turned grey, and the trains had stopped running.

My father cried as he watched the Hill disappear before his eyes. The big farmer was sympathetic, but merely shrugged his shoulders; times were hard, and anyway, what use was a lump of rock to a farmer? Father sold his smallholding, his sheep and his goats, and took a job in the quarry. Very soon Seamus and myself followed. Seamus was installed at the weighbridge, assisting with the dockets because he had a head for figures. Somebody must have reckoned I had a head for heights – because I was given the task of carrying the equipment for the men who set the charges. Every evening, just before six, the birds rose from the Hill like dust from a carpet, and shortly afterwards the silence was shattered by a series of thunderclaps. Another bit of the Hill gone west.

It was shortly after my eighteenth birthday that Frances and Seamus died. To the jaws of New York I ran; my solitary suitcase filled with the rags of my youth, a bottle of holy water, and a pile of Kit Carson and Johnny Mac Brown comics. Away from the grief choking my lungs, and the red staining the grey rocks brown. Away from the haunted thing staring at me from every reflective surface, and from the silent screams riding every breeze that tugged at the Hill’s battered face. Away to Uncle Willie.

I saw many sights in New York, dreamed a thousand dreams, and knew real loneliness for a time. The icy mistrals that periodically sweep down the great canyons of Broadway and the Bronx were warm compared to me. I was a rock. I was an island. My days were spent constructing fashionable patios around stucco-ed buildings with ornate entrances and moneyed owners, my nights in Uncle Willie’s counting house. In time, his small building firm became my large construction company. Occasionally, when time permitted, I would come and watch the Hill grow smaller.

………………

All quiet here now. The bulldozers and bedlam-makers have gone. And so too has the Hill. Erased from the skyline in thirty short years. A covering of topsoil hides some of the scars; here and there conifers and shrubs attempt to breathe new life into the pock-marked, lunar-like surroundings. In the centre a square of green, vivid against the drab background, seems strangely out of place. Even more incongruous is the white building, rising like a Phoenix from the embers, its five fluted columns standing like sentinels beneath its awning, its flanks guarded by a colonnade of progressively-sloping evergreens.

The pub still stands at the crossroads, grown larger and more prosperous over the years, and the creamery has expanded to become a cheese-making factory. Of the level crossing and the railway there is no visible sign, although a cursory search would reveal the tracks still intact beneath the undergrowth. Most of the cottages have gone; replaced by new houses – many more of them – and the city, once more than five miles away, is now within spitting distance.

I look around me and shiver suddenly. The ghosts of yesterday clamouring for attention once more. The Red Devils scampering up that ungainly lump of granite. Voices drifting in the wind; “look what I found, look what I found!”. Dogs, rabbits, burrows, names etched in flint. Soft hair, silky thighs, music and laughter aloft on the breeze. Then another excursion. This time two people heading for the secret place, and another figure – hidden – watching. An explosion. The evening turning crimson. Two coffins submerged beneath a garden of flowers. A funeral cortege stretching further than the eye could see…Oh Frances, why? You and Seamus…Oh God! I never meant for it to end like that…

A voice at my elbow brings me back to the present.

“I found the keys in my briefcase. Everything alright?”

I look at the man wearing the thick horn-rimmed glasses. Was this tubby little estate agent really the boy I had played cowboys and indians with all those years ago? Staked out on a warm rock as the rest of us chanted and danced around him?

“Yes”, I smile, “Everything is fine now Josie”.

He hands me the bunch of jangling keys. “The keys to the Hill, Bernie. Welcome home”

end (c) Tom O’Brien

FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK

https://hastingsonlinetimes.co.uk/arts-culture/arts-news/pogues-musical-back-at-the-stables

FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK

WARTS AN’ ALL by Tom Power & Tom O’Brien

WARTS AN’ ALL by Tom Power & Tom O’Brien

NATIONAL POETRY DAY

A couple of poems for National Poetry Day

MY CAR NOW TALKS TO ME

Hello

Goodbye

Raising the lights like a stage curtain

Playing little movies

Serenading me with melodies

The welcome – farewell experience

They call it

“An emotionally resonant experience”

And that digital note of appreciation

“Thank you for driving a hybrid”

As if it was something…well

Unconnected with this thing on four wheels.

And those door handles

Illuminating when they sense my presence

The needles on the instruments

Snapping to attention as I open the door

There’s a welcoming theme

Part Hollywood soundtrack

Part plane swoosh

And that puddle lamp!

A welcome mat of light.

My car is a robot I think

With a personality not just in its body

But also in its behaviour.

“How can I help you?”

It asks now

As I prepare for take-off.

I really feel like telling it

To shut the fuck up

But I don’t want to hurt its feelings.

THE GREEN FORGOTTEN VALLEYS

Those green forgotten valleys,

No longer can be seen

Lying hidden behind the tall fir and larch

That have made these brown hills green

Relentlessly marching down the hills

Burying everything in their wake

The dead are long gone from this place

The pike no longer in the lake

The houses just hollow shells now

Where the past ghosts eerily through

The vacant windows and doors

With rotted frames and jambs that once were new.

Back then there was no silence, only the sound

Of human laughter, and bird-calls to each other

The dogs growling at a wayward sheep.

And children’s scrapes kissed better by their mother

Nature is having the last laugh now

Soon there will be no trace of us at all

As the trees come marching down the hillside

No one hears the lonesome curlew’s call.